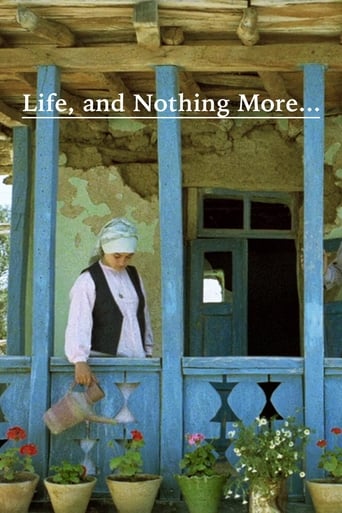

Life, and Nothing More… (1992)

After the earthquake of Guilan, a film director and his son travel to the devastated area to search for the actors from the movie the director made there a few years previously. In their search, they see how people who have lost everything in the earthquake still have hope and try to live life to the fullest.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

People are voting emotionally.

Mostly, the movie is committed to the value of a good time.

The best films of this genre always show a path and provide a takeaway for being a better person.

Close shines in drama with strong language, adult themes.

When the 1990 Manjil–Rudbar earthquake hit and killed fifty thousand people, director Abbas Kiarostami made the decision to return to the Iranian village of Koker and find the little boys who were part of the cast of his earlier masterpiece, Where is the Friend's Home? It is during that trip that Kiarostami was struck by inspiration, going back to retrace his steps and film his own journey as his second entry into the eventual Koker trilogy. What follows is a surprisingly hopeful film about the vast reserves of resiliency in the face of hardship for these Iranian citizens, and how the end, life simply must go on. The events are captured in an unadorned verite style, with harsh, slightly overexposed natural light and a free camera, recalling the neorealist and non-fiction roots of Kiarostami's early career. Those familiar with his work will recognise one of his favoured shots; an extreme wide overhead, surveying the tiny car with amusement as it slowly chugs through the ravaged countryside. This is usually coupled with diegetic sound that contradicts the distance of the shot; we can hear Kiarostami (his actor) and his son right in our ears, although we are much too far away. The moment gently mocks their progress, the foolish ideal that such an insignificant machine could instantly make the arduous journey (think of that horizontal wide shot, with the gigantic, jagged cracks in the ground dwarfing their vehicle). Kiarostami used the same shot in his later masterpiece The Wind Will Carry Us, cutting deeper with his critique. Here he eventually allows his surrogate a POV shot through the windscreen, as if to consider his perspective too, but does this only further emphasise the lack of forward momentum, the fixed perspective? To truly find what he is looking for, he must exit the car and walk on his own two feet, not merely make enquiries through the window as if he was peering into a zoo exhibit. There is little artifice beyond this point, except for the bits where Kiarostami uses the film's self-reflexivity to play with ideas of cinematic representation and truth behind the screen. They bump into Mr Ruhi, who played a character in one of Kiarostami's previous films, and is now purposefully transporting a urinal to another place of need in the aftermath of the earthquake's destruction. When the director queries him on his new home, he nonchalantly replies: "Well, that was my house in the movie." The big one with the terrace was just for show. Later, though, he does complain that the film made him look older and uglier than he really is. His moment is Kiarostami's apology and admission of his past inaccuracies, of how the movies have conditioned us to make certain assumptions of the reality presented on the screen. Now he slowly but surely trudges on, remarking that even in the wake of such devastating disaster someone will still have need of a urinal - something that the director seemingly bypasses as his son runs off into the bushes. In The Wind Will Carry Us, a crew arrived in a rural village to film the imminent death ritual of an elderly woman, but found that life would not bow over so easily to their gaze. In Life, and Nothing More..., a director and his son search endlessly for two boys and the village of Koker, but do not ever find it. But what Kiarostami does find in the latter that was scarce in the former is a deeply humanist and optimistic view of life, of people not weeping and cursing at the sky, but shouldering this burden and carrying on best they can. Listen to how innocently Puya attempts to rationalise the earthquake, and how his perspective is scattered within everyone they meet: of tragedy reaffirming all that is precious in our lives. That little pearl comes from the same boy whose face is earlier emblazoned by darkness and the opening credits as they enter a tunnel, sleeping on his back and unaware of their destination. And witness the gentle beauty in the film's final shot, where Kiarostami and a stranger help one another up a winding, zig-zagging hill. Their toil across the landscape is hardly easier after all, but now the shot is not of mockery, but celebrating their compassion in the face of adversity.

"I believe the films of Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami are extraordinary. Words cannot relate my feelings." - Akira Kurosawa Abbas Kiarostami directed "Where is the Friend's Home?" in 1987, the tale of an 8 year old boy who embarks on a quest to find his friend's house. The film took place in Koker, a village in northern Iran. The village was devastated three years later by the 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake. This earthquake prompted Kiarostami's real-life return to Koker, a journey in which he attempted to locate the young stars of his 1987 film, all of whom were actual Koker residents. Kiarostami's 1992 film, "Life and Nothing More", reconstructs this journey. His 1994 film, "Through the Olive Trees", is partially about the making of "Life and Nothing More". This trilogy of films marks a larger shift in Kiarostami's filmography: a movement away from neorealism and toward postmodern self-reference.Unlike most "natural disaster movies", "Life and Nothing More" quickly forgoes condescending gestures. Kiarostami has little time for either noble sufferers or canned sorrow. Instead he focuses on two characters, an unnamed film-maker (a stand-in for Kiarostami himself) and his young son, both of whom travel to Koker in a rickety yellow car. Landslides and traffic hamper their journey, but pretty soon they arrive in Koker. They then embark on a mission to locate the two young boys who appeared in the director's "Where is the Friend's House?" Both films offer similar journeys and tell tales of, not human beings conquering adversity (both quests fail; the boy never found his friend's house, and the film-makers never find the boys), but of characters persevering despite obstacles. Climbing is thus a repeated motif, Kiarostami treating us to long-shots of vehicles trekking up mountains and characters who either push unrelentingly onward or clamber out of rubble. Kiarostami's camera lingers on debris and collapsed concrete, Koker's residents like solitary weeds sprouting weakly upwards after a drought.Later, a woman tells us she lost her home and family, but declines outside assistance. She will get by on her own. "If the dead could return," another haggard character tells us, "they would appreciate life more." This character, who plays himself playing himself, was cast in Kiarostami's previous film, where he was made to look "older and uglier". "That is not art," he states. "If you make an old man young and handsome, that's art!" "Life and Nothing More" traces something similar; an attempt to tease out something handsome and dignified amidst perpetual calamity. But this reflexivity is then complicated. The man may have been made "uglier" on film, but, as he now reveals, the previous film lied by suggesting that he lives in a house rather than a simple tent. This tension – art which ennobles, searches for truths, but also lies and perverts – increasingly obsesses Kiarostami, as his films become less neorealist, more Goddardian and more reflexive. Indeed, increasingly his films don't ask us to enter worlds but instead obsessively revolve around characters who skirt around the edges of worlds, places and actions. They are spectators like us. The car in "Life and Nothing More" is itself a glorified camera mount, shielding both us and its occupants from the outside, even as we and our heroes try in vain to establish contact with the outside world. Kiarostami's films may be structured as games of searching, finding and looking, but are increasingly about the very postmodern problem of seeing, subjectivity and the limits of knowledge. He's, in a sense, the Iranian Atom Egoyan.Postmodern cinema plays up self-reference, homage, pastiche, nihilistic self-absorption and a detachment from the social. But while Kiarostami's films increasingly call attention to themselves as representation, and are increasingly self-reflexive (they do not quote films outside of Kiarostami's filmography), they mostly lack the smug sense of self-conscious sophistication (and knowingness) which postmodernists trade in. Where central to postmodernism is the gap between the image of reality and what is reality – with the sign always victorious over essence – Kiarostami's work searches out that essence with the assumption that everything is capable of being at least somewhat true or containing truths.The third film in what is often called "the Koker trilogy" (it is also three steps meta-removed from the original film), "Through the Olive Trees" opens with a movie director (Kiarostami's surrogate) conducting a casting call. He's looking for a female villager to play the leading role in his new film. He finally selects a woman called Tehereh. She will play a bride. Off-set Tehereh is similarly courted by a man, Hossein, who seeks to make her his bride. The film's great joke is that Hossein is also cast in the film within the film and that Tehereh refuses to speak to him as a co-star; he's poor, homeless and illiterate and Tehereh's parents disapprove of his marriage requests. What Kiarostami is concerned with, though, is the way comedy conceals tragedy, the way the fictional film conceals what it also unintentionally documents and how this tug-of-war itself results in Koker's rebuilding in the wake of the quake.In all three films, Kiarostami's visuals are wonderfully minimalist, though this tone often gives way to either surreal moments or visual gags. Recall surreal shots of a man carrying a urinal, footpaths which zig-zag up hill-faces and the way matter-of-fact dialogue offered by various civilians clash with the earthquake's horrible aftermath.Heavyweight film-makers like Godard, Kurosawa and Antonioni (Kiarostami's "Close Up" in many ways is influenced by Antonioni's "Blow Up") have all expressed a fondness for Kiarostami's films. Kiarostami's "Life and Nothing More" was retitled "And Life Goes On..." in the West, a less gloomy title which, in a way, sums up the kind of art-house sentimentality that is responsible for Kiarostami's popularity. Kiarostami's next feature was the audience polarising "Taste of Cherry".8.5/10 – Worth two viewings.

There is a long intro before the title. A film director and his son are shown driving in a small beat-up car to northern Iran soon after the 1990 earthquake. When the car enters a long tunnel, the camera keeps rolling and on the darken screen the titles finally appear.The film director is nominally Kiarostami, but played by an actor. Typical for his films, the documentary genre blurs with the fictional account. The devastation that we see from the moving car is real, though the lamentations we witness are probably staged, which does not diminish the sense of suffering of the affected local communities.The impetus of this travelogue through a torn landscape is to locate at least one of the kids that was his main character in one of his previous films, "Khaneh-je doost kojast?". That quest is the director's central preoccupation, so much so he does not recognize another boy, who he gives a lift to, that had a secondary role in that film. If you see the aforementioned film, you will clearly remember the face.The quest is made difficult by roads that have been gutted or blocked by rock and earth slides, and by the steep mountainous terrain of his goal, the small town of Koker. As he gets tantalizing close, we root for him.The way the film ends may be disappointing to some, but I found that it matched the title of the film, "And Life Goes On". For the survivors of the earthquake there is mourning for the dead, but at the same time the 1990 World Soccer Cup is going on. What team will make it to the final? While houses have to be rebuilt, it is also important that TV antennas be lifted so that all can see the games in the evening. The director will make more films but now he is concerned about the well-being of that child actor. So life goes on, the quest must go on. There is no ending.

This is the transition from Kiarostami's films about children into his more adult, philosophically ponderous phase (and his bridging of the gap between characters searching on foot, as in the first of the trilogy, "Where is the Friend's Home," and within cars). As with all of Kiarostami's films, it's just beautiful to look at, not so much the way he films it (although this film continues his favorite shot of action taking place extremely far away), but what is filmed. For this reason I almost feel like I'm blinded by the director's name on the film, giving his films such high marks, because he doesn't really DO anything that you can point to. There is no startling mise-en-scene (the nature exists anyway, regardless of his camera). But he repeatedly and consistently creates a tranquil, pure, loving feeling in me. It has to do with his soul: he's putting it up there every time. Not autobiographically, but tonally. It has nothing to do with words like "craft" or "quality." The simple gesture of a child wanting to raise a grasshopper is enough for Kiarostami to be considered a great realist, an observer. And his film is a connector of people. It might sound simple to say, but for a Westerner with no real idea of what life is like in Iran -- or better, not life, but people -- the simple depiction of it that shows, "Hey, they're basically like us," is invaluable. That's the difference between artists who share what is and artists who create what isn't. And more immediately, within the film, he deals with the public tragedy as great connector, whether it's an earthquake or an act of terrorism. And for us Westerners whose first real impression of that came with 9/11, this film will ring true -- and be remarkable if we consider that things like this happen over there all the time. (Which possibly explains why our main character never seems all that shocked by anything he sees; when a woman cries for her family, he nods his head, but doesn't seem terribly affected by her tears.) One character here asks what Iran has done to anger God and cause the earthquake, but there is little religiosity in the film. Unlike certain recent American films, this film does not have a tendency toward hand-wringing and overwrought seriousness reaching toward the skies. That scene itself is understated like the entire film. The characters here are not spiritual ciphers. They're utterly practical. As with Kiarostami's two greatest films, "Close-Up" and "Taste of Cherry," the film becomes brilliant when it breaks from its placid realism into self-reference: the main character pulls out a picture of a boy who acted in the real film "Where is the Friend's Home?" and asks strangers where this real boy is, who he says played a role in the film. Is this a real earthquake? Is this actor really harmed? Is this a documentary? Is the main actor playing Kiarostami; is Kiarostami filming this from the passenger seat? Are they really out looking for this boy? But as with those two masterpieces, it's this that borders on insufferable, smirking cleverness on Kiarostami's part that makes me question the so-called honesty of his films. (I find his interviews pretentious and evasive.) Is it possible to be a self-referencing deconstructionist and reveal human truths, not just reveal "the nature of cinema," in an attempt to be the Iranian Godard? This is what lessens my enjoyment of his films, because it lowers my trust. Kiarostami asks a lot of us. "Okay, admit the first film was openly a film, but accept this as a closed film, until I tell you it's a documentary..." There are other flaws. It does get "cute" at times, as when the main character repeats his son's question at a later time ("Why is it coming out of a tap?"). And the boy seems preternaturally wise -- part of the film's "message" is not to discount kids' wisdom: the boy questions the validity of the claim that God caused the earthquake, shocking one woman that he and his father come in contact with throughout their travels. However, there is so much richness elsewhere (and I'm willing to accept that the layering of the self-reference adds to the film, even if it makes it momentarily annoying) that you can move beyond its flaws (which, honestly, I would accept pretty easily in another film; with Kiarostami you have expectations in the clouds). I'm particularly interested in the way children (and the child experience as remembered or experienced by an adult) are presented on screen, and I'm continually ecstatic that we have Kiarostami contributing to this. (That the main character's son describes one boy from "Where is the Friend's Home?" by his eyes is appropriate, as when we see him they are indeed strikingly beautiful.) The film is also an interesting comment on what happens to people after they work -- Falconetti comes to mind. And the ending is already a classic: it's like the swimming pool scene in "Nostalghia" in tone. Does what happen happen because the film has to end that way, or because of the human spirit? (This is one of the few scenes where music plays under it.) Even though the movie has no end, only a means, it moves forward like a good documentary. Even though time is not indicated (there are few, if any lapses; time is experienced, as in Tarkovsky), it moves along at a nice pace -- not so much in that the story is brisk, more in that we've settled into its own rhythm. There is no "story," only the story of film as experience. Lots of Big statements could be inferred from the film -- it's about an endless journey with no resolution to a place they don't know how to get to (college students, get your pens out) -- but I take it directly. 9/10