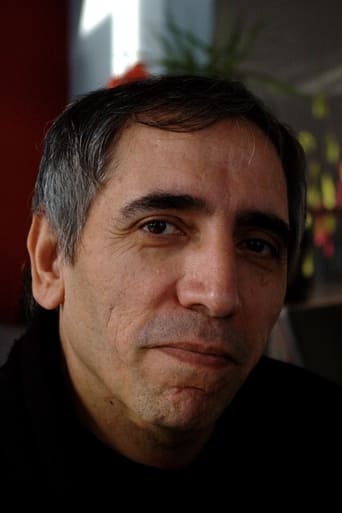

A Moment of Innocence (1996)

A semi-autobiographical account of Makhmalbaf's experience as a teenager when, as a 17-year-old, he stabbed a policeman at a protest rally. Two decades later, he tracks down the policeman he injured in an attempt to make amends.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Lack of good storyline.

it is the rare 'crazy' movie that actually has something to say.

It’s sentimental, ridiculously long and only occasionally funny

Great story, amazing characters, superb action, enthralling cinematography. Yes, this is something I am glad I spent money on.

Though Mohsen Makhmalbaf eventually established a reputation as one of Iran's foremost filmmakers from the late 1980s, his early life was tumultuous: when he was 17, he stabbed a police officer at a protest against the Shah's regime and spent the next four years in prison, only being released after the Shah's overthrow. His 1996 film NUN VA GULDOON ("Bread and Flowerpot", released in the English-speaking world as "A Moment of Innocence") looks back at this episode from his youth, attempting to jointly evoke both the red-hot passion against political injustice of a young man and his older, wiser understanding that such clumsy violence was hardly a productive way to solve the world's problems.The result is intricately constructed as a film-within-a-film. As it opens, we see the now 40-year-old policeman (Mirhadi Tayebi) visiting Tehran to ask Makhmalbaf for a part in one of his films to make up for the stabbing two decades before. Makhmalbaf, playing himself, decides to make a film loosely based on the stabbing. He chooses a young man (Ali Bakhsi) to play his younger self, and he then asks the policeman to choose an actor as the young version of himself. The policeman, who has a thuggish look and is bitter about never being offered parts in films besides villain ones, chooses a handsome guy to represent himself, but he is then overruled by the filmmaker who chooses a much more boyish-looking and vulnerable young man (Ammar Tafti), emphasizing just how young both Makhmalbaf and the policemen were at the time. This layer of NUN VA GULDOON broadly pokes fun at what Makhmalbaf's life had become after his rise to fame in Iran, having to endlessly deal with ordinary people who fancied themselves actors and were desperate to appear on screen. Much of this part of the film was shot concurrently with his effort SALAAM CINEMA, which is entirely about the film casting process.Makhmalbaf and the policemen begin coaching the actors playing their younger selves and we see those young people beginning to act their roles, as well as a young lady (Maryam Mohamadamini) playing a girl that the policeman was in love with at the time. In a magical realist fashion, the layers of the film shift in the middle of scenes: one moment we are watching actors play roles, the next moment it is as if the viewer is really seeing what happened in the mid-1970s. It is this magical intertwining of past and present that made NUN VA GULDOON such a powerful experience for me. The ending, which has been fairly praised as "the greatest freeze-frame since Truffaut's LES 400 COUPS", is just as much a work of art in itself as any still from a Tarkovsky film.Except for Makhmalbaf himself and Moharram Zaynalzadeh in a supporting role as his cameraman, none of the people in the film were trained actors. With Mirhadi Tayebi as the policeman, this is a weak part of the film: he delivers his lines in a stilted way and it is hard to suspend disbelief. With the others, however, Makhmalbaf made a smart choice, as Ammar Tafti and Ali Bakhsi are convincing in their roles, but there is still a youthful awkwardness and authenticity about them that would might have been lost if they were professionals. Most dazzling of all, however, is Maryam Mohamadamini as the love interest. She's a magnetic screen presence, and as the film leads to its incredible ending, she deftly conveys so much of the suspense and drama through gestures alone. It's a huge loss to cinema that she apparently never acted again.In spite of the film's limitations in terms of some of the acting and the limited resources Makhmalbaf had to work with when making the film, I found NUN VA GULDOON a moving film and that last freeze-frame literally breathtaking. I'd recommend this to any lover of cinema.

As if fellow Iranian director Kiarostami's exemplary intertwining of fact and fiction of a Makhmalbaf real-life story in "Close-Up" weren't enough, Makhmalbaf himself ups the ante of creative filmmaking a few years later: Focus is a moment in his young idealistic life where he stabbed a guard during the Iranian revolution, resulting in several years of jail time for him before he eventually emerged as one of the leading Iranian filmmakers. But it's not just an autobiographical detail he wants to shed light on, Makhmalbaf films a documentary on top of a pseudo-documentary (or is it the other way round?), it's a heavily symbolic re-interpretation of what happened, why and how, a look into an aspect of reality. In the process a transcendence of the actual situation ensues with an almost mythical truth buried in the film's final scene. Makhmalbaf accomplishes the feat by re-enacting said moment with no other than the actual stabbed guard (now out of money), who coaches a young actor to play himself - while the former guard is being filmed by the director doing so. Simultaneously to that Makhmalbaf casts actors meant to portray his own perspective of the events, not without revealing insights, and the whole effort culminates in the filming of that crucial stabbing scene: Welcome to a film in a film, a reality in a reality, a blending of fact and fiction in a most fruitful and enlightening way, social, historical and political commentary included. How much of what ended up on screen was actually planned, is for the viewer to decide, but if you're looking for creative minds Makhmalbaf's use of the medium will keep you enthralled throughout."Excuse me, what time is it?" we hear Makhmalbaf's accomplice ask the guard at the end of the film, the air pregnant with suspenseful anticipation of what is going to happen. So, what time is it? It's two decades after the original incident and an Iranian filmmaker has just delivered his masterpiece. And when the moment arrives the picture freezes, saving a moment in time for eternity that could only happen on film. But in a way, it's all real.

In the 1970's director Mohsen Makhmalbaf was a militant against the Shah; during a disturbance he tried to take a policeman's gun producing a struggle that resulted in him stabbing that officer a crime for which he then served time in prison. While away, he educated himself and was released from prison to be an influential voice within Iranian cinema. For this film he decided to use actors to recreate this event in his life with young actors playing himself and the policeman. However the director decides to split the actors each man gets the young version of himself, and their own camera to reconstruct events from their point of view. The experiment works producing further pain and anger.This is a hard film to describe, far less review. Basically this is a film about making a film of a real event; and if that wasn't twisted enough, it is really two separate films made from two points of view, although to describe the story as a film is a bit too much, really the focus is recreating the one fateful moment the two men came together. Now I'm not sure if this is all as real as it appears to be (particularly did the officer only find out that his "love" was a plant at the moment he did in the film?) but if it is staged then it is done very convincingly. The story works and manages to do both aspects well at the same time something that the film makes look easy but must have been very difficult to pull off. It is engaging for that reason but the fact that it is real people and a real story only makes it more interesting, not to mention how touching and downright tragic parts of it are. The final image is the most tragic both young boys want to avoid the violence and want specific things for that moment other than the stabbing, just as (we assume) both wanted in reality but, despite the final shot of the film we know that the reality was the violent outcome.The direction is superb, weaving together this tale with different actors and blending realities with such confidence. The "performances" are good, although please remember that I don't know if these were staged or as we saw them. If they were staged then high praise indeed should go to Tayebi, because he is convincing in his emotion, his passion and, ultimately, his heartbreak. The others do well around him but for me, he was the loser of the film and I ended feeling a great deal for him partly due to his presence on the screen.I have done a bad job of reviewing this film and for that I am sorry. I have failed to describe how engaging it was, how the blending of the "filming of the re-enactment" and the "film of the filming of the re-enactment" merge but still are obvious and separate. I have failed to really do justice to the characters and the emotions involved in the story. However, my words should not detract from this very strong film that demands attention but rewards it in spades you should try to find it.

This is the greatest among the dozen or so Makhmalbaf titles I have seen. I was stunned that a movie so thematically complex (politics, history, redemption, etc.) can be conveyed with a superb lightness of touch. When you watch it, you really feel like you're watching a comedy. Only gradually does the movie reveal its many layers, culminating in a final freeze-frame that might be the BEST in all of cinema. More people should watch this movie! (It's certainly a lot more fun than anything by Abbas Kiarostami - a man who is more of a moral philosopher than a film-maker per se).